The rasputitsa refers to the biannual seasons when unpaved roads

become difficult to traverse in parts of Belarus, Russia and

Ukraine. The word may be translated as the "quagmire season"

because during this period the large flatlands become extremely

muddy and marshy, as do most unpaved roads. The term applies to

both the "spring rasputitsa" and "autumn rasputitsa" and to the

condition of the roads during those seasons. The rasputitsa occurs

more strongly in the spring due to the melting snow but it usually

recurs in the fall due to frequent heavy rains.

The rasputitsa seasons of Russia are well known as a great

defensive advantage in wartime. Napoleon found the mud in Russia to

be a very great hindrance in 1812. During the Second World War the

month-long muddy period slowed down the German advance during the

Battle of Moscow, and may have helped save the Soviet capital, as

well as the presence of "General Winter", that followed the autumn

rasputitsa period.

#

Von Weichs's 2 Army was still clearing up the area of the

encircled Bryansk Front near the Desna and had been left far behind

the spearhead of the advance and out of touch with the main enemy.

In the second week in October 1941, the clearing operations having

been completed, its three infantry corps began their long march

eastwards through the streaming rain and mud. The men were

exhausted after the break-in battles and mopping-up operations near

Bryansk, but there was no question of giving them even a few days'

rest. Pursuit eastwards was the order of the day. Tired and

verminous and soaked to the skin, boots and socks never dry, the

infantry trudged slowly southeast from Bryansk along the Orel

highway.

Infantry was the only arm capable of moving by its own efforts,

even though this movement was hardly eight miles a day. With its

few possessions on its back it moved itself, fed itself and

quartered itself by living off the land, improved its own tracks

and built its own light bridges. Not only did it march, but it

found the willing hands which pulled the horses out of mud-filled

shell holes and gullies, and provided the heaving backs which got

the ditched wagon wheels turning again; yet without the horse the

infantry itself would have been lost.

Most roads and tracks had disappeared and those remaining were

so few in number that several divisions were allocated to a single

route, this congestion slowing down the rate of march. No wheeled

motor vehicles accompanied the columns. Although the progress of

the dismounted men was painfully slow, that of the horses in

harness was even slower. In the end the infantry companies were

ordered on ahead and they left behind them the vehicle-loaded

stores, heavy radio and ammunition and the horse-drawn anti-tank

guns and artillery. Fleeter of foot, they began to overtake other

units and formations, no further effort being made to keep to a

march table, so that regiments and divisions became mixed and

broken up.

The hamlets through which the columns passed were crammed with

German troops; too often the towns and bigger villages had been

destroyed in the fighting or gutted by the local inhabitants, who

looted all materials and fixtures which could possibly be carried

off. For the most part the troops remained out at night in the rain

and the cold; sleep was out of the question. Although movement was

not delayed by the enemy or by mines, it took von Weichs's marching

infantry formations fourteen days to cover 125 miles. Even then,

most of the equipment had been left behind.

By 26 October, when the van of 2 Army had reached the area

between Mtsensk and Kursk, it was directed to thrust on Efremov,

Elets and the area north of Voronezh. Von Weichs, having crossed

Guderian's lines of communication from left to right, was moving

away from him and could no longer cover the 2 Panzer Army right

flank.

Immediately to the north of von Weichs's 2 Army, 52 German

Infantry Division moved near the inter-army boundary towards Kaluga

on the far southern flank of von Kluge's 4 Army. The formation had

started from Sukhinichi, leaving the forest belt behind it, when,

on 13 October, the rains began in earnest. The general service army

carts were ditched because they were slung too low, and Russian

farm vehicles were seized from the fields. The loads which could

not be carried forward were abandoned and the remaining horses

pooled in order to provide spare teams. Only two light guns in each

battery were taken on, together with their limbers, each piece

being dragged forward by ten horses, while the unharnessed animals

brought up the rear.

Within two days the horses, up to the knees and sometimes the

girths in mud, had lost their shoes, but in the soft going could

manage without them. The infantrymen, whose calf boots were

frequently sucked from their legs as they waded on, knee deep in

water, were not so fortunate. Their boots were already in pieces.

After the first day's march the horse-drawn guns and baggage, light

though it was, could not keep up with the men, and the troops went

rationless except for the tea and potatoes looted from the farms.

No longer could they rely on the support of the gun and mortar in

clearing up enemy resistance.

Unwittingly, they longed for the coming of the front and the

winter.

LINK

June 1941 - the largest invasion ever mounted - Babarossa - and the great conflict that ensued....

Tuesday, February 24, 2015

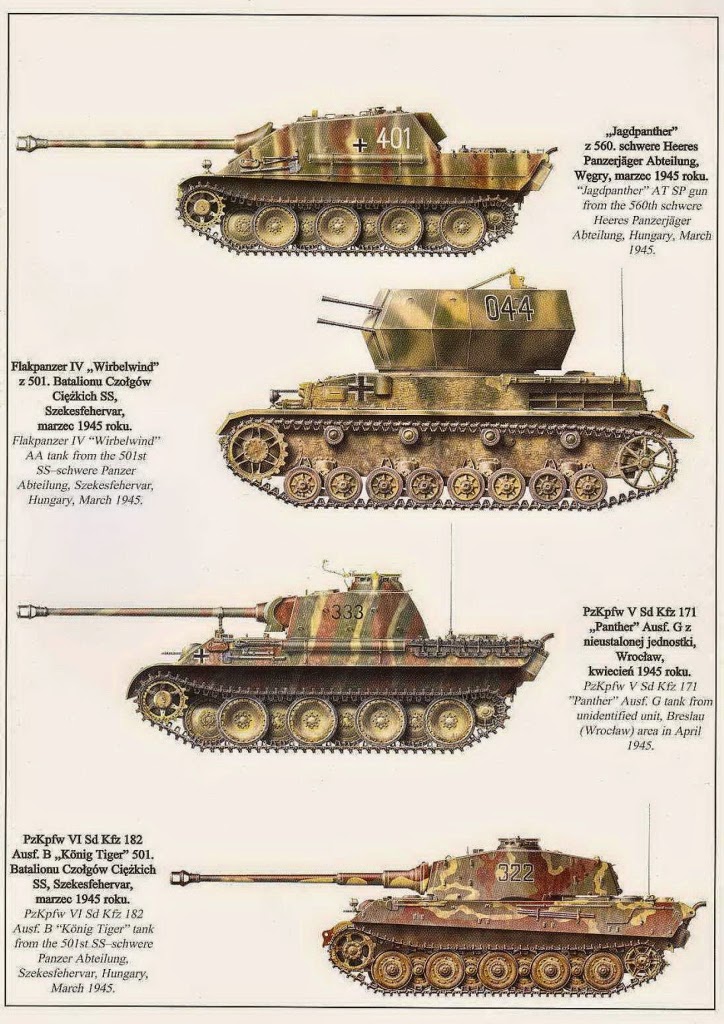

German Panzers 1943

The second main tank used by the Panzerwaffe at this time was the Pz.Kpfw. IV. Already by the beginning of June 1943 - when there were 932 Pz. Kpfw. IIIs and 1 ,047 Pz. Kpfw. IVs available - this tank was being used in the Panzerwaffe units in greater numbers than the Pz. Kpfw. III . In this photo we see a platoon of Pz. Kpfw. IV Ausf. H with three-tone camouflage passing by the ruins of a town in the Kursk area. The Pz.Kpfw. IV was better in combat than the Soviet T-34, and the quality of German steel was better than Soviet's.

The best medium tank of the second part of WWI I - the Pz. Kpfw. V Panther - suffered from some technical problems in the middle of 1943. Nevertheless, it was a very dangerous weapon to the Soviet tank crews, who appreciated the tank very much. Here a soldier poses with a Pz.Kpfw. V Ausf. D belonging to the staff of an Abteilung. The tank is marked with the two-color (red outlined with white) tactical marking "A13". Note the camouflage of the tank; it is covered with solid coat of brown and green spots, so the dark yellow color is only occasionally visible. The Ausf. D had no machine gun in the glacis plate, this being the standard for the tanks and self-propelled guns of the Panzerwaffe during this period of the war.

Tank units used Tigers during the fighting on the Kursk bulge - two battalions and four companies with 146 Pz. Kpfw. Vis. They lost 33 tanks, but destroyed about 30 times more Soviet tanks, many other weapons, as well as field installations. They lead almost every assault and gave immediate destructive support for attacking infantry. This photo shows one of these Tigers, which carries the tactical number "321 " and is painted in a two-color camouflage scheme.

Russian emigration in Germany – Post 1917

Many Russian emigrants left Germany in 1933, or soon after; among them were Simon Dubnov, Grigorii Landau, Semen Frank, Leonid Pasternak, Roman Gul’ and Vladimir Nabokov. Many others put their faith in the anti-Bolshevism of the new regime and did not reject it until much later, as was the case with the philosophers Ivan Il’in and Boris Vysheslavtsev. A good number offered their services as Russian National Socialists to various organizations of the new order – not always to their satisfaction, as the Third Reich viewed the emigrants as moaners and schemers, an egoistical bunch who needed watching and bringing into line. But a good many of them collaborated with the Nazi authorities up to the bitter end, while dozens of those who had once sought refuge in Berlin were later hunted down and killed all over Europe – this was the fate of Mikhail Gorlin and Raisa Bloch in Paris, and of Simon Dubnov in Riga, to name but three.

For the majority of the emigrants the onset of Nazi rule merely meant that life went on, with community activities, functions, balls, anniversaries, job-hunting and the like. Even Russian Jews in Berlin were long unaware of the seriousness of their situation. In 1936 the ‘Russian Intermediary Office’ was reconstituted under the direction of General Biskupskii, above all, in order to sort out the rival emigrant organizations. It also meant that it had to accept a number of language directives, such as those issued after the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939 and the invasion of Poland, under which they had to agree that the pact was entirely in the interest of the Russian people.

The decisive turning point did not, of course, come until the start of the German invasion of the Soviet Union on 22 June 1941. Now many emigrants saw themselves presented with the opportunity to return home and to turn the slogan of the ‘anti-Bolshevik struggle’ into deeds – alongside the Wehrmacht, the SS and the Special Units.

A good number of emigrants collaborated with the Germans in order to work towards this goal. Russian emigrants in countries occupied by the Wehrmacht reported to the Russian Intermediary Offices in Paris, Warsaw and Brussels, took the oath of loyalty to the Third Reich (as Generals Golovin, Kusonskii and von Lampe did) and then reported to their units, while suspicious or uncooperative members of the emigrant community were harassed and sometimes even imprisoned. The attitude of the German authorities to the emigrants was, though, inconsistent and ambivalent: on the one hand the emigrants were needed, on the other hand they were regarded as unreliable – after all, it was Hitler’s watchword that ‘none but Germans should be allowed to bear arms.’ The deployment of Russian emigrants was therefore subject to various limitations: emigrants of the first generation and former members of the Red Army found it difficult to agree on things, some German organizations had great suspicion of the ‘Russians’ as such, while the competing plans of the Germans lacked uniformity. The idea of forming a Russian Liberation Army under General Andrei Vlasov, who had been captured in July 1942, was postponed time and again because of German anxiety about arming foreigners, and it was not deployed until spring 1945. Emigrants from the inter-war years joined the Vlasov army and the Wehrmacht as translators, specialists and commanders of Russian voluntary units; about 1,500 Russian emigrants from France joined the Wehrmacht, while ca. 1,200 from Germany were assigned to it as translators. As a precautionary measure lists were put together of emigrant experts who would be able to take part in the administration and reconstruction of the occupied territories. Hundreds of Russian, Ukrainian, Georgian and other emigrants worked as translators in the Reich Ministry for the Occupied Eastern Territories, the Organizations Todt and Speer, in German counter-intelligence and the Reich Propaganda Ministry. Senior officers from the White Russian emigration (Generals Arkhangel’skii, von Lampe, Dragomirov, Golovin, Kreiter, Cossack atamans Abramov, Balabin and Shkuro) joined the Vlasov movement, as did representatives of new organizations that had only been formed in exile, but this too was not without its problems, as the suspicious Gestapo followed the emigrants’ every step.

Some of the leading representatives of emigration who collaborated with the Wehrmacht were captured after the victory of the Red Army in the East, deported and tried in Moscow or Kharkov, and subsequently executed. Those who could flee to the Western zones of Germany after the War disappeared in the second wave of refugees.

ROA (Vlasov's army)

Private of the ROA (Vlasov's army),

1942-45

01 - Dutch field jacket with ROA collar tabs and shoulder straps, Heeres eagle on the right breast

02 - M-40 trousers

03 - dog tag

04 - M-34 forage cap with ROA badge

05 - boots

06 - M-42 leggins

07 - German main belt with ammo pouches

08 - M-24 grenade

09 - M-31 canteen

10 - bayonet

11 - M-39 webbing

12 - M-35 helmet with camouflage net

13 - "Novoye Zhizn" magazine for the "Eastern" volunteers

14 - 7,62 mm Mosin 1891/30 rifle

Russia was far from a monolithic structure. It contained numerous diverse ethnic groups, many of which had long histories of resenting Russian suzerainty and domination. Combined with the long standing hatred of Russia, the new Soviet regime was often even more hated, even by the Russians, so when the Germans invaded, their initial reception was often one of liberator than one of conqueror. Deserters appeared in the hundreds before German units offering their services in any capacity and they were taken in gladly. They were given the names "Hilfsfreiwilliger" (Volunteer Helpers) or Hiwis for short. Initially, their functions were the various menial tasks such as cooking, digging latrines, officers' batmen, etc., but more than once they jumped into combat roles when the opportunity arose. Hundreds of the Hiwis were gradually sucked into the role of combatant, despite the lack of orders and the German ethnic attitudes of the period.

The 134th Infantry Division began openly enlisting Russians in July 1941. Other divisions refrained from such overt violation of Hitler's orders, but more than willingly took the Russians on an unofficial basis. During the winter of 1941/42 the first Osttruppen or Eastern Troops were formed. By early 1942 six battalions of Ostruppen were formed in Army Group Center under Oberst von Tresckow. These units were given territorial designations, like Volga, Berezina, and Pripet. Initially they were used in the rear on anti-partisan operations with the security divisions, but slowly they were brought forward into the front lines.

In early 1942 racist elements of the German hierarchy brought this to Hitler's attention. He responded to the movement by prohibiting the use of Russian "sub humans" as soldiers and on 2/10/42 issued a Fuhrer Order that limited their use of those existent units to rear area operations only. Despite his obvious displeasure, the Osttruppen continued to expand. The OKH was to authorize the use of Hiwis up to 10% to 15% of divisional strength and by August 1942 official regulations were issued governing uniforms pay, decoration, and insignia. By early 1943 an estimated 80,000 Russians were serving the Wehrmacht in Ostbataillonen.

The formation of Russian units in the German army would have been quite limited had not the Soviet General Vlassov been captured in July 1942. He had been a prominent general after the war erupted, but in March 1942 he was ordered to liberate Leningrad with the 2nd Soviet Assault Army. His attack failed and his army of nine infantry divisions, six infantry brigades, and an armored brigade were surrounded, abandoned by Stalin, and crushed, leaving the Germans with 32,000 prisoners. Amongst the German High Command there had always some hope of forming a Russian army to assist them in the conquest of Soviet Russia. As time progressed, it became apparent that Vlassov was the ideal man to form this army.

As the war progressed and the German effort in Russia began failing, Hitler was eventually persuaded to permit the formation of the army. The first steps occurred in August 1942 when General Koestring formed an Inspectorate which was to organize Caucasian troops. Koestring, however, ignored this limitation and took all volunteers possible. When Koestring retired in January 1943 the post of General der Ostruppen was created and given to General Hellmich, who had no previous experience with the Russians. Fortunately, Hellmich and Koestring's service overlapped and the two men agreed on Koestring's earlier decisions.

The Osttruppen was absorbing not only Caucasians, but Ukrainians, Russians, Azberjainis, and Turkistanis. In January 1944 Koestring, now apparently out of retirement, took over from Hellmich with the new title General der Freiwilligen Verbaende (General of Volunteer Units). In the meantime, Hitler had authorized the formation of a Russian army under Vlassov. In November 1942 a Russian National Committee was established in Berlin with Vlassov serving as Chairman. It then issued the Smolensk Manifesto, calling for the destruction of Stalinism, the conclusion of an honorable peace with Germany, and Russian participation in the "New Europe."

The German Army intelligence then proceeded to drop copies of leaflets over the Russian lines, as well as a carefully planned accident which resulted in their being dropped over German lines as well. It appears that Hitler had forbidden any release of this in the German press. During the winter of 1942/43, faced with the destruction of the 6th Army in Stalingrad and Rommel's expulsion from North Africa, Hitler began to reconsider the role he had allocated to Vlassov's Russkaia Osvoboditelnaia Armiia or ROA.

The desertion rate from the Soviet army rose to 6,500 in July 1943, compared to 2,500 the previous year, as a result of ROA propaganda and the future looked bright. However, in September 1943 Hitler announced that the ROA was to be dissolved. The German generals pleaded with him, pointing out that the Russian front would collapse, as there were currently 78 Ost battalions, 122 companies, one regiment and innumerable supply, security, and other units then serving with the German army, not to mention the thousands of Hiwis in the German units. Certainly there were 750,000 Russians then serving in the German army and some estimates go so far as to suggest that 25% of the German army on the Russian front was made up of ethnic Russians.

A screaming and raging Hitler was eventually brought to compromise and only those units whose loyalty was suspect were to be disbanded and the rest would be transferred to the West. This, being left in Wehrmacht hands, the disbandings were limited to 5,000 men and serious procrastination prevented many transfers westwards. However, by October 1943 large numbers of Ostruppen did begin moving west. This was accomplished by exchanging Ost Battalions for German battalions in the west. These Ost battalions were then formally incorporated into the German divisions where they were assigned.

The morale of the Osttruppen began to collapse. Vlassov was persuaded to write them an open letter announcing these transfers were only a temporary expediency and hinted at bigger and better things. When the allies invaded Normandy they were startled to find that many of their German prisoners were, in fact, Russians and soon had 20,000 ROA prisoners in custody. Though Himmler refused to believe Koestring's reports, at that time there were 100,000 eastern volunteers in the Luftwaffe and Navy and another 800,000 in the German Army.

The continuing reversal of German military hopes was slowly bringing even the SS around to reconsidering the desirability of Russian troops. In the east the SS was, by late 1943, regularly rounding up 15-20 year olds to serve as Flak helpers. There was discussion of the creation of an Eastern Moslem SS Division and several Slavic legions were forming in the SS. Himmler soon began considering himself as the leader of the "Army of Europe" and began taking any non-German human material he could find into his hands. It was not long before he saw Vlassov's ROA as another force that could be added.

Himmler approached Vlassov and proposed the formation of a Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossi or K.O.N.R.) It was to be allowed to raise an army of five divisions, two of which were to be raised immediately. The personnel would be drawn from the existing ROA units and from among the Ostarbeiter then in Germany. The first two units formed were placed under Vlassov's command on 1/28/45, the 600th and 650th Russian Divisions. In Neuren an airforce or air division, was organized that consisted of an air transport squadron, a reconnaissance squadron, a flak regiment, a paratrooper battalion, and a flying training unit. This force of some 4,000 men was assigned to General V.I. Maltsev. On 2/1/45 Goering formally handed this division over to Vlassov's command.

By March 1945 the KONR numbered some 50,000 men. The Cossack Cavalry Corps was promised to Vlassov by Himmler, as was the Russian Guard Corps in Serbia, but in fact neither was ever placed under his command. The KONR fought its first battle in February 1945 when a force of the 600th Division attacked in Pommerania and its engagement was a complete success. Hundreds of Soviet soldiers changed sides and joined it. In March it moved to the Oder front and was ordered to attack the Soviet army near Frankfurt. However, it was so pounded by the Soviets that it withdrew to the south and back into Czechoslovakia. On 5/5/45 the Czech communists began a revolt in Prague and Buniachenko ordered the 600th Division to assist them. Their assistance was refused by the Czechs and, as the war ended the next day, the division was taken prisoner by the Americans. The 650th Division, except for one regiment, were captured by the Russians and either executed or sent into the Russian Gulag. Vlassov was snatched from American hands by the Russians, suffered through a short show trial, and was quickly executed along with the major leaders of the KONR.

599TH RUSSIAN BRIGADE: Formed in April 1945 in Aalborg, Denmark, as part of the Liberation Russian Army under Vlassov. It contained:

1/,2/,3/1604th Grenadier Regiment (from 714th (Russian) Grenadier Regiment) 1/,2/,3/1605th Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/1606th Grenadier Regiment

The division was intended to be expanded to form the 3rd Vlassov Division.

600TH (RUSSIAN) INFANTRY DIVISION Formed on 12/1/44 as part of the Russian Liberation Army under Vlassov with what was to have become the 29th Waffen SS Grenadier Division (1st Russian). On 2/28/45 it contained:

1/,2/1601st Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1602nd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1603rd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/,4/1600th Artillery Regiment 1600th Division Support Units

650TH (RUSSIAN) DIVISION Formed in March 1945 as part of Vlassov's Russian Liberation Army. The division was organized with prisoners of war and contained, on 4/5/45:

1/,2/1651st Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1652nd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1653rd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/,4/1650th Artillery Regiment 1650th Divisional Support Units

The division was not fully formed and remained in Munsingen until overrun. On 17 January 1945 the organization of the 650th Infantry (Russian) Division was established as follows:

DIVISION STAFF: Division Staff (2 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Mapping Detachment 1650th (mot) Military Police Detachment (3 LMGs)

1651ST INFANTRY REGIMENT: REGIMENTAL STAFF Staff Staff Company (3 LMGs) 1 Signals Platoon 1 Engineer Platoon (6 LMGs) 1 Reconnaissance Platoon (3 LMGs) 1 Signals Platoon 2 BATTALIONS, each with 3 Infantry Companies (9 LMGs ea) 1 Heavy Company (8 HMGs, 4 75mm infantry support guns, 1 LMG & 6 80mm mortars)

13TH INFANTRY SUPPORT COMPANY: (2 150mm leIG, 1 LMG, 8 120mm mortars & 4 LMGs)

14TH PANZERJAGER COMPANY (54 Panzerschreck, 18 Reserve Panzerschreck & 4 LMGs)

1652ND INFANTRY REGIMENT: same as 1651st 1653RD INFANTRY REGIMENT: same as 1651st

1650TH (MOUNTED) RECONNAISSANCE BATTALION: 4 Squadrons, each with (9 LMGs, 2 80mm mortars)

1650TH PANZERJAGER BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 (mot) Staff Company (1 LMG) 1st Company (12 75mm PAK & 12 LMGs) 2nd (armored) Company 14 Assault Guns (sturmgeschutz) & 16 LMGs Detachment captured Russian tanks 3rd (mot) Flak Company (9 37mm Flak guns & 5 LMGs)

1650TH ARTILLERY BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 1ST, 2ND & 3RD BATTALIONS, each with: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 2 105mm leFH Batteries (4 105mm leFH & 4 LMGs ea) 1 75mm Battery (6-75mm guns & 3 LMGs) 4TH BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 2 150mm sFH Batteries (6-150mm howitzers & 4 LMGs ea)

1650TH (BICYCLE) PIONEER BATTALION 2 (bicycle) Pioneer Companies, each with: (2 HMGs, 9 LMGs, 6 flame throwers & 2 80mm mortars) 1 Pioneer Company (2 HMGs, 9 LMGs, 6 flame throwers & 2 80mm mortars)

1650TH SIGNALS BATTALION: 1 (mixed mobility) Telephone Company (4 LMGs) 1 (mixed mobility) Radio Company (2 LMGs) 1 (mixed mobility) Signals Supply Detachment (2 LMGs)

1650TH FELDERSATZ BATTALION: 1 Supply Detachment 5 Replacement Companies, with a total of: (50 LMGs, 12 HMGs, 6 80mm mortars, 1 120mm mortar 1 75mm leIG, 1 75mm PAK, 1 20mm/37mm Flak, 2 flame throwers, 1 105mm leFH 18 , 6 Panzerschrecke, & 56 Sturm Gewehr 41

1650TH DIVISIONAL SUPPORT REGIMENT: SUPPLY TROOP: 1650th (mot) 120 ton Transportation Company (4 LMGs) 1/,2/1650th Horse Drawn (30 ton) Transportation Companies (2 LMGs ea) 1650th Horse Drawn Supply Platoon OTHER: 1650th Ordnance Troop 1650th (mot) Vehicle Maintenance Troop 1650th Supply Company (3 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Field Hospital 1650th (mot) Medical Supply Company 1650th Veterinary Company (2 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Field Post Office

In a parallel formation to the ROA and KONR another large force of Russians was formed in March 1942 by German Intelligence. This force was the Versuchsverband Mitte (Experimental Formation of Army Group Center). Though officially known as Abwehr Abteilung 203 the unit was to have several names - Verband Graukopf, Boyarsky Brigade, Russian Special Duty Battalion, Ostintorf Brigade, and finally the Russian National People’s Army (Russkaia Natsionalnaya Narodnaya Armiya or RNNA). The unit was started when a Russian émigré, Sergi Ivanov, recruited several prominent Russian prisoners of war and other Russian exiles, to the German cause. Ivanov, acting as a liaison officer for the Abwehr, worked with Igor Sakharov, son of a White Russian General and émigré to Germany, and slowly they organized a force of 3,000 former prisoners of war.

By December 1942 they had 7,000 men training. A brigade was formed consisting of four battalions, an artillery battalion, and an engineer battalion. The organization of the units was based on the Russian model. In August 1942 Colonel Boyarsky took command in December Feldmarschal von Kluge inspected the brigade, was pleased with what he saw, and expressed his pleasure with its actions in combat in the German rear in May 1942. He then stated that he would issue the unit German uniforms and weapons and split it into a number of infantry battalions, which would be assigned to various German combat divisions. This offhanded command shattered the brigade's morale and 300 men promptly deserted. It had seen itself as the cadre of a Russian army of liberation. Despite their protests, the brigade was broken into the 633rd, 634th, 635th, 636th, and 637th Ost Battalions and employed in anti-Partisan operations.

01 - Dutch field jacket with ROA collar tabs and shoulder straps, Heeres eagle on the right breast

02 - M-40 trousers

03 - dog tag

04 - M-34 forage cap with ROA badge

05 - boots

06 - M-42 leggins

07 - German main belt with ammo pouches

08 - M-24 grenade

09 - M-31 canteen

10 - bayonet

11 - M-39 webbing

12 - M-35 helmet with camouflage net

13 - "Novoye Zhizn" magazine for the "Eastern" volunteers

14 - 7,62 mm Mosin 1891/30 rifle

Russia was far from a monolithic structure. It contained numerous diverse ethnic groups, many of which had long histories of resenting Russian suzerainty and domination. Combined with the long standing hatred of Russia, the new Soviet regime was often even more hated, even by the Russians, so when the Germans invaded, their initial reception was often one of liberator than one of conqueror. Deserters appeared in the hundreds before German units offering their services in any capacity and they were taken in gladly. They were given the names "Hilfsfreiwilliger" (Volunteer Helpers) or Hiwis for short. Initially, their functions were the various menial tasks such as cooking, digging latrines, officers' batmen, etc., but more than once they jumped into combat roles when the opportunity arose. Hundreds of the Hiwis were gradually sucked into the role of combatant, despite the lack of orders and the German ethnic attitudes of the period.

The 134th Infantry Division began openly enlisting Russians in July 1941. Other divisions refrained from such overt violation of Hitler's orders, but more than willingly took the Russians on an unofficial basis. During the winter of 1941/42 the first Osttruppen or Eastern Troops were formed. By early 1942 six battalions of Ostruppen were formed in Army Group Center under Oberst von Tresckow. These units were given territorial designations, like Volga, Berezina, and Pripet. Initially they were used in the rear on anti-partisan operations with the security divisions, but slowly they were brought forward into the front lines.

In early 1942 racist elements of the German hierarchy brought this to Hitler's attention. He responded to the movement by prohibiting the use of Russian "sub humans" as soldiers and on 2/10/42 issued a Fuhrer Order that limited their use of those existent units to rear area operations only. Despite his obvious displeasure, the Osttruppen continued to expand. The OKH was to authorize the use of Hiwis up to 10% to 15% of divisional strength and by August 1942 official regulations were issued governing uniforms pay, decoration, and insignia. By early 1943 an estimated 80,000 Russians were serving the Wehrmacht in Ostbataillonen.

The formation of Russian units in the German army would have been quite limited had not the Soviet General Vlassov been captured in July 1942. He had been a prominent general after the war erupted, but in March 1942 he was ordered to liberate Leningrad with the 2nd Soviet Assault Army. His attack failed and his army of nine infantry divisions, six infantry brigades, and an armored brigade were surrounded, abandoned by Stalin, and crushed, leaving the Germans with 32,000 prisoners. Amongst the German High Command there had always some hope of forming a Russian army to assist them in the conquest of Soviet Russia. As time progressed, it became apparent that Vlassov was the ideal man to form this army.

As the war progressed and the German effort in Russia began failing, Hitler was eventually persuaded to permit the formation of the army. The first steps occurred in August 1942 when General Koestring formed an Inspectorate which was to organize Caucasian troops. Koestring, however, ignored this limitation and took all volunteers possible. When Koestring retired in January 1943 the post of General der Ostruppen was created and given to General Hellmich, who had no previous experience with the Russians. Fortunately, Hellmich and Koestring's service overlapped and the two men agreed on Koestring's earlier decisions.

The Osttruppen was absorbing not only Caucasians, but Ukrainians, Russians, Azberjainis, and Turkistanis. In January 1944 Koestring, now apparently out of retirement, took over from Hellmich with the new title General der Freiwilligen Verbaende (General of Volunteer Units). In the meantime, Hitler had authorized the formation of a Russian army under Vlassov. In November 1942 a Russian National Committee was established in Berlin with Vlassov serving as Chairman. It then issued the Smolensk Manifesto, calling for the destruction of Stalinism, the conclusion of an honorable peace with Germany, and Russian participation in the "New Europe."

The German Army intelligence then proceeded to drop copies of leaflets over the Russian lines, as well as a carefully planned accident which resulted in their being dropped over German lines as well. It appears that Hitler had forbidden any release of this in the German press. During the winter of 1942/43, faced with the destruction of the 6th Army in Stalingrad and Rommel's expulsion from North Africa, Hitler began to reconsider the role he had allocated to Vlassov's Russkaia Osvoboditelnaia Armiia or ROA.

The desertion rate from the Soviet army rose to 6,500 in July 1943, compared to 2,500 the previous year, as a result of ROA propaganda and the future looked bright. However, in September 1943 Hitler announced that the ROA was to be dissolved. The German generals pleaded with him, pointing out that the Russian front would collapse, as there were currently 78 Ost battalions, 122 companies, one regiment and innumerable supply, security, and other units then serving with the German army, not to mention the thousands of Hiwis in the German units. Certainly there were 750,000 Russians then serving in the German army and some estimates go so far as to suggest that 25% of the German army on the Russian front was made up of ethnic Russians.

A screaming and raging Hitler was eventually brought to compromise and only those units whose loyalty was suspect were to be disbanded and the rest would be transferred to the West. This, being left in Wehrmacht hands, the disbandings were limited to 5,000 men and serious procrastination prevented many transfers westwards. However, by October 1943 large numbers of Ostruppen did begin moving west. This was accomplished by exchanging Ost Battalions for German battalions in the west. These Ost battalions were then formally incorporated into the German divisions where they were assigned.

The morale of the Osttruppen began to collapse. Vlassov was persuaded to write them an open letter announcing these transfers were only a temporary expediency and hinted at bigger and better things. When the allies invaded Normandy they were startled to find that many of their German prisoners were, in fact, Russians and soon had 20,000 ROA prisoners in custody. Though Himmler refused to believe Koestring's reports, at that time there were 100,000 eastern volunteers in the Luftwaffe and Navy and another 800,000 in the German Army.

The continuing reversal of German military hopes was slowly bringing even the SS around to reconsidering the desirability of Russian troops. In the east the SS was, by late 1943, regularly rounding up 15-20 year olds to serve as Flak helpers. There was discussion of the creation of an Eastern Moslem SS Division and several Slavic legions were forming in the SS. Himmler soon began considering himself as the leader of the "Army of Europe" and began taking any non-German human material he could find into his hands. It was not long before he saw Vlassov's ROA as another force that could be added.

Himmler approached Vlassov and proposed the formation of a Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia (Komitet Osvobozhdeniia Narodov Rossi or K.O.N.R.) It was to be allowed to raise an army of five divisions, two of which were to be raised immediately. The personnel would be drawn from the existing ROA units and from among the Ostarbeiter then in Germany. The first two units formed were placed under Vlassov's command on 1/28/45, the 600th and 650th Russian Divisions. In Neuren an airforce or air division, was organized that consisted of an air transport squadron, a reconnaissance squadron, a flak regiment, a paratrooper battalion, and a flying training unit. This force of some 4,000 men was assigned to General V.I. Maltsev. On 2/1/45 Goering formally handed this division over to Vlassov's command.

By March 1945 the KONR numbered some 50,000 men. The Cossack Cavalry Corps was promised to Vlassov by Himmler, as was the Russian Guard Corps in Serbia, but in fact neither was ever placed under his command. The KONR fought its first battle in February 1945 when a force of the 600th Division attacked in Pommerania and its engagement was a complete success. Hundreds of Soviet soldiers changed sides and joined it. In March it moved to the Oder front and was ordered to attack the Soviet army near Frankfurt. However, it was so pounded by the Soviets that it withdrew to the south and back into Czechoslovakia. On 5/5/45 the Czech communists began a revolt in Prague and Buniachenko ordered the 600th Division to assist them. Their assistance was refused by the Czechs and, as the war ended the next day, the division was taken prisoner by the Americans. The 650th Division, except for one regiment, were captured by the Russians and either executed or sent into the Russian Gulag. Vlassov was snatched from American hands by the Russians, suffered through a short show trial, and was quickly executed along with the major leaders of the KONR.

599TH RUSSIAN BRIGADE: Formed in April 1945 in Aalborg, Denmark, as part of the Liberation Russian Army under Vlassov. It contained:

1/,2/,3/1604th Grenadier Regiment (from 714th (Russian) Grenadier Regiment) 1/,2/,3/1605th Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/1606th Grenadier Regiment

The division was intended to be expanded to form the 3rd Vlassov Division.

600TH (RUSSIAN) INFANTRY DIVISION Formed on 12/1/44 as part of the Russian Liberation Army under Vlassov with what was to have become the 29th Waffen SS Grenadier Division (1st Russian). On 2/28/45 it contained:

1/,2/1601st Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1602nd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1603rd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/,4/1600th Artillery Regiment 1600th Division Support Units

650TH (RUSSIAN) DIVISION Formed in March 1945 as part of Vlassov's Russian Liberation Army. The division was organized with prisoners of war and contained, on 4/5/45:

1/,2/1651st Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1652nd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/1653rd Grenadier Regiment 1/,2/,3/,4/1650th Artillery Regiment 1650th Divisional Support Units

The division was not fully formed and remained in Munsingen until overrun. On 17 January 1945 the organization of the 650th Infantry (Russian) Division was established as follows:

DIVISION STAFF: Division Staff (2 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Mapping Detachment 1650th (mot) Military Police Detachment (3 LMGs)

1651ST INFANTRY REGIMENT: REGIMENTAL STAFF Staff Staff Company (3 LMGs) 1 Signals Platoon 1 Engineer Platoon (6 LMGs) 1 Reconnaissance Platoon (3 LMGs) 1 Signals Platoon 2 BATTALIONS, each with 3 Infantry Companies (9 LMGs ea) 1 Heavy Company (8 HMGs, 4 75mm infantry support guns, 1 LMG & 6 80mm mortars)

13TH INFANTRY SUPPORT COMPANY: (2 150mm leIG, 1 LMG, 8 120mm mortars & 4 LMGs)

14TH PANZERJAGER COMPANY (54 Panzerschreck, 18 Reserve Panzerschreck & 4 LMGs)

1652ND INFANTRY REGIMENT: same as 1651st 1653RD INFANTRY REGIMENT: same as 1651st

1650TH (MOUNTED) RECONNAISSANCE BATTALION: 4 Squadrons, each with (9 LMGs, 2 80mm mortars)

1650TH PANZERJAGER BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 (mot) Staff Company (1 LMG) 1st Company (12 75mm PAK & 12 LMGs) 2nd (armored) Company 14 Assault Guns (sturmgeschutz) & 16 LMGs Detachment captured Russian tanks 3rd (mot) Flak Company (9 37mm Flak guns & 5 LMGs)

1650TH ARTILLERY BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 1ST, 2ND & 3RD BATTALIONS, each with: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 2 105mm leFH Batteries (4 105mm leFH & 4 LMGs ea) 1 75mm Battery (6-75mm guns & 3 LMGs) 4TH BATTALION: 1 Staff 1 Staff Battery (1 LMG) 2 150mm sFH Batteries (6-150mm howitzers & 4 LMGs ea)

1650TH (BICYCLE) PIONEER BATTALION 2 (bicycle) Pioneer Companies, each with: (2 HMGs, 9 LMGs, 6 flame throwers & 2 80mm mortars) 1 Pioneer Company (2 HMGs, 9 LMGs, 6 flame throwers & 2 80mm mortars)

1650TH SIGNALS BATTALION: 1 (mixed mobility) Telephone Company (4 LMGs) 1 (mixed mobility) Radio Company (2 LMGs) 1 (mixed mobility) Signals Supply Detachment (2 LMGs)

1650TH FELDERSATZ BATTALION: 1 Supply Detachment 5 Replacement Companies, with a total of: (50 LMGs, 12 HMGs, 6 80mm mortars, 1 120mm mortar 1 75mm leIG, 1 75mm PAK, 1 20mm/37mm Flak, 2 flame throwers, 1 105mm leFH 18 , 6 Panzerschrecke, & 56 Sturm Gewehr 41

1650TH DIVISIONAL SUPPORT REGIMENT: SUPPLY TROOP: 1650th (mot) 120 ton Transportation Company (4 LMGs) 1/,2/1650th Horse Drawn (30 ton) Transportation Companies (2 LMGs ea) 1650th Horse Drawn Supply Platoon OTHER: 1650th Ordnance Troop 1650th (mot) Vehicle Maintenance Troop 1650th Supply Company (3 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Field Hospital 1650th (mot) Medical Supply Company 1650th Veterinary Company (2 LMGs) 1650th (mot) Field Post Office

In a parallel formation to the ROA and KONR another large force of Russians was formed in March 1942 by German Intelligence. This force was the Versuchsverband Mitte (Experimental Formation of Army Group Center). Though officially known as Abwehr Abteilung 203 the unit was to have several names - Verband Graukopf, Boyarsky Brigade, Russian Special Duty Battalion, Ostintorf Brigade, and finally the Russian National People’s Army (Russkaia Natsionalnaya Narodnaya Armiya or RNNA). The unit was started when a Russian émigré, Sergi Ivanov, recruited several prominent Russian prisoners of war and other Russian exiles, to the German cause. Ivanov, acting as a liaison officer for the Abwehr, worked with Igor Sakharov, son of a White Russian General and émigré to Germany, and slowly they organized a force of 3,000 former prisoners of war.

By December 1942 they had 7,000 men training. A brigade was formed consisting of four battalions, an artillery battalion, and an engineer battalion. The organization of the units was based on the Russian model. In August 1942 Colonel Boyarsky took command in December Feldmarschal von Kluge inspected the brigade, was pleased with what he saw, and expressed his pleasure with its actions in combat in the German rear in May 1942. He then stated that he would issue the unit German uniforms and weapons and split it into a number of infantry battalions, which would be assigned to various German combat divisions. This offhanded command shattered the brigade's morale and 300 men promptly deserted. It had seen itself as the cadre of a Russian army of liberation. Despite their protests, the brigade was broken into the 633rd, 634th, 635th, 636th, and 637th Ost Battalions and employed in anti-Partisan operations.

Later Panzer Divisions – East

The motorized divisions were effectively the elite of the German infantry. In 1942-43 the 14,319-strong M1940 Motorized Divisions, with two motorized infantry regiments and motorized divisional support units and services, each received a Panzer and an anti-aircraft or assault gun battalion. On 23 June 1943 they were redesignated M1944 Armoured Infantry Divisions (singular: Panzergrenadierdivision), 14,738 strong with two motorized armoured infantry regiments (each 3,107 men) and one Panzer battalion (602 men and 52 tanks); seven divisional support units - one motorized artillery regiment (1,580 men), and field replacement (973 men), armoured reconnaissance (1,005 men), anti-tank (475 men), motorized anti-aircraft (635 men), motorized engineer (835 men) and motorized signals (427 men) battalions; plus 1,729-strong divisional services.

The Panzer divisions steadily lost effectiveness as their strength and weaponry declined. On 24 September 1943 all 15,600-strong M1941 Panzer Divisions were reorganized as M1944 Panzer Divisions. Each had an establishment of 14,013 German troops and 714 Hilfswillige, in a two-battalion Panzer regiment (2,006 men, 165 tanks), a 2,287-strong armoured infantry regiment (one battalion on half-tracks), and a 2,219 motorized armoured infantry regiment; divisional support units were an armoured artillery regiment (1,451 men), and armoured field replacement (973 men), anti-aircraft (635 men), armoured reconnaissance (945 men), armoured anti-tank (475 men), armoured engineer (874 men) and armoured signals (463 men) battalions; 1,979 personnel provided additional divisional services.

On 24 March 1945 all armoured divisions were ordered to be reorganized as 11,422-strong M1945 Panzer Divisions, with a mixed 1,361-strong Panzer regiment with one Panzer (767 men and 52 tanks) and one half-track-mounted armoured infantry (488 men) battalion, two motorized armoured infantry regiments (each 1,918 men), and support units and services as before.

Barbarossa - Panzer Divisions

The first weeks of Barbarossa saw the Panzers make rapid advances and Soviet forces taking heavy losses, outshining the German achievements of 1940. However, problems soon surfaced. The lack of a suitable road network slowed down the German follow-up infantry and supplies, with the result that the Panzers failed to complete the encirclement of the enemy. The infantry took longer than expected to mop up enemy forces and the Panzer Divisions became worn out; to compound matters, the Soviet mobilization came sooner than expected. Autumn, with its unfavourable climate, soon bogged down Operation Taifun, the German assault on Moscow. Time and space - two unforeseen factors - took their toll, and eventually the Soviet counter-offensive of December 1941 brought the German Army and the Panzerwaffe face to face with their first defeat, which was to have dire consequences for the Germans.

It did not take long before the war on the Eastern Front exposed the shortcomings of German doctrine. The lack of an adequate road network and accurate maps, the erroneous estimates for fuel consumption (60,000 litres of fuel daily for a 200-tank Panzer Regiment soon turned into 120,000 and 180,000 litres daily) and the wear and tear on the vehicles greatly influenced the Panzer Divisions' capabilities, along with the inability of the infantry to keep pace with the armoured advance. Until 27 June 1941 Panzergruppen 2 and 3 advanced 320km with a daily rate of 64km, but this shrank to 20km a day in early July. Likewise, 8. Panzer Division's daily rate of advance was 7Skm until 26 June, but this dropped to 32km in the first half of July. Autumn brought the first bad weather, and the resulting quagmire, which restricted the Panzer Divisions to movement on the main roads, made manoeuvre and encirclement practically impossible. Winter combined with improvements to the Soviet defences, with their anti-tank guns deployed forward, further reduced the mobility of the Panzer Divisions. Eventually, the severe losses suffered during the first Soviet counter-offensive and the subsequent reorganization of the Panzer Divisions crushed any German hopes of victory.

End of 1941

The blitzkrieg team was frayed. The Luftwaffe’s operational losses had been compounded by the problems of maintenance at improvised forward air strips, and crew fatigue the system refused to recognize. The 2nd Air Fleet, Army Group Center’s opposite number, had approximately 170 single-engine fighters, about the same number of bombers, and 120 ground attack planes. The artillery’s material losses had been limited, but its horses were dying, its vehicles were breaking down, and its ammunition reserves were limited. The infantry was tired. Average divisional strengths had been reduced by a quarter—more in the rifle companies. Morale was still high; and to some degree the shortage of men was compensated by material. Increasing numbers of 50mm antitank guns, effective against T-34s, were coming on line. Army Group Center had 14 battalions of the assault guns that had demonstrated their worth over and over again in all sectors. In the final analysis, however, the attack on Moscow would go as far as the panzers could carry it.

The code name was Taifun, and reality approached rhetoric. The initial intention had been to redeploy 4th Panzer Group on Hoth’s left and launch a two-pronged attack. The rapid victory at Kiev enabled Guderian’s group to be brought up on the right. When the number was finalized, Bock had fourteen panzer and eight motorized divisions, more than 1,000 tanks on a 500-mile front. The panzers were not what they had been on June 21. Casualties had been heavy and replacements inadequate. But they remained the cream of the army: tempered but not yet brittle, respecting their enemy but still convinced they had the Soviets’ measure.

Guderian’s panzer divisions were still at about half their assigned tank strength. The situation in Groups 3 and 4 was better. Two of Hoepner’s divisions had even enjoyed full, albeit brief, refits in France. The problem was sustainability. Shifting Panzer Groups 2 and 4 quickly and smoothly showcased the quality of German staff planning and traffic management, but it came with a price in wear and tear. Hitler had ordered engine production allocated to new vehicles, and the army group had received only 350 replacements. The shortage of other vehicles exceeded 20 percent. Fuel consumption was outstripping the Reich’s production capacity. Existing supplies remained difficult to move forward due to the still-inadequate rail system.

Pavlov’s House

The Battle of Stalingrad was a major event during World War II

in which Nazi Germany attacked the Soviet Union for control of

Stalingrad in southwestern Russia. The battle was marked by extreme

brutality, disregard for military law, and massive casualties on

both sides, nearly two million people died. At one point, the Third

Reich captured 90% of the city, but the Soviets prevailed in the

fight. During the battle, the Red Army attempted to occupy

strategic positions throughout the city. One of these places was

Pavlov’s House, which is a four-story building in the middle of

Stalingrad and constructed parallel to the Volga River.

Pavlov’s House is located on a cross-street and provided a 1 kilometer line of sight to the north, south, and west of Stalingrad. In September 1942, the house was attacked and captured by the Germans. In response, the Red Army ordered a platoon led by Junior Sgt. Yakov Pavlov to take it back. After an intense battle where 26 of the 30 Soviets in the platoon were killed, the Red Army was able to capture Pavlov’s House. The house was then fortified and turned into a stronghold. The building was equipped with machine guns, anti-tank rifles, and mortars. It was surrounded by four layers of barbed wire, minefields, and the Soviets set up machine-gun posts in every available window. The supplies were brought into the fort through an underground communications trench.

During the battle, the Germans attacked Pavlov’s House several times a day. Each time the Red Army would unload a barrage of machine gun fire and kill dozens of Nazis. The Russians mounted a PTRS-41 anti-tank rifle on the roof of Pavlov’s House and destroyed a large number of tanks. The structure came to symbolize the Soviet resistance and was marked as a fortress on several Nazi maps. For his actions in the war, Yakov Pavlov was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. Soviet general Vasily Chuikov famously said that the Germans lost more men trying to take Pavlov’s House than they did Paris. After the war, Pavlov’s House was reconstructed and turned into an apartment building. A memorial set of bricks from the battle remains at the site and is located on the East end of the house facing the Volga River.

Pavlov’s House is located on a cross-street and provided a 1 kilometer line of sight to the north, south, and west of Stalingrad. In September 1942, the house was attacked and captured by the Germans. In response, the Red Army ordered a platoon led by Junior Sgt. Yakov Pavlov to take it back. After an intense battle where 26 of the 30 Soviets in the platoon were killed, the Red Army was able to capture Pavlov’s House. The house was then fortified and turned into a stronghold. The building was equipped with machine guns, anti-tank rifles, and mortars. It was surrounded by four layers of barbed wire, minefields, and the Soviets set up machine-gun posts in every available window. The supplies were brought into the fort through an underground communications trench.

During the battle, the Germans attacked Pavlov’s House several times a day. Each time the Red Army would unload a barrage of machine gun fire and kill dozens of Nazis. The Russians mounted a PTRS-41 anti-tank rifle on the roof of Pavlov’s House and destroyed a large number of tanks. The structure came to symbolize the Soviet resistance and was marked as a fortress on several Nazi maps. For his actions in the war, Yakov Pavlov was awarded the title Hero of the Soviet Union. Soviet general Vasily Chuikov famously said that the Germans lost more men trying to take Pavlov’s House than they did Paris. After the war, Pavlov’s House was reconstructed and turned into an apartment building. A memorial set of bricks from the battle remains at the site and is located on the East end of the house facing the Volga River.

Soviet WWII Uniforms

Private, Red Army, 1939-41

01 - Model 1940 "ushanka" cap

02 - Model 1935 coat, with service branch insignia on the collar tabs

03 - felt boots

04 - main belt

05 - 7,62 mm Tokarev SVT-40 rifle

06 - bayonet

07 - ammo pouches

08 - bag for the gas mask

09 - folding shovel

NKVD lieutenant, 1940-41

01 - Model 1935 NKVD cap

02 - Model 1925 sweatshirt, lieutenant insignia on the red (NKVD) collar tabs, metal stars on the sleeves

03 - NKVD service breeches

04 - boots

05 - main belt

06 - holster for the Nagant 1895 revolver

07 - model 1932 map pouch

08 - "Veteran NKVD soldier" badge, established 1940

09 - Order of the Red Star

10 - military ID book

11 - ammo for the Nagant revolver

Soviet infantry, 1941

01 - Model 1940 steel helmet

02 - "Telogreika" jacket

03 - field trousers

04 - boots

05 - 7,62 mm Mosin 91/30 rifle

06 - rifle oiler

07 - Model 1930 ammo pouches

08 - personal dressing

09 - military ID

10 - synthetic leather map pouch

Soviet infantry officer, 1943

01 - model 1943 "gimnastiorka" sweatshirt, officers' version

02 - model 1935 breeches

03 - model 1935 forage cap

04 - model 1940 helmet

05 - model 1935 officers' belt and webbing

06 - holster for the Nagant 1895 revolver

07 - map pouch

08 - officers' boots

Red Army officer, Reconnaissance unit, ca. 1943

01 - Model 1935 forage cap

02 - camouflage clothing, autumn variant

03 - 7,62 mm PPS-43 SMG

04 - tarpaulin ammo pouch for 3 PPS magazines

05 - Model 1935 officers' belt

06 - leather holster with 7,62mm TT pistol

07 - Model 1940 assault knife

08 - Adrianov compass

09 - personal dressing

10 - officers' boots

01 - Model 1940 "ushanka" cap

02 - Model 1935 coat, with service branch insignia on the collar tabs

03 - felt boots

04 - main belt

05 - 7,62 mm Tokarev SVT-40 rifle

06 - bayonet

07 - ammo pouches

08 - bag for the gas mask

09 - folding shovel

NKVD lieutenant, 1940-41

01 - Model 1935 NKVD cap

02 - Model 1925 sweatshirt, lieutenant insignia on the red (NKVD) collar tabs, metal stars on the sleeves

03 - NKVD service breeches

04 - boots

05 - main belt

06 - holster for the Nagant 1895 revolver

07 - model 1932 map pouch

08 - "Veteran NKVD soldier" badge, established 1940

09 - Order of the Red Star

10 - military ID book

11 - ammo for the Nagant revolver

Soviet infantry, 1941

01 - Model 1940 steel helmet

02 - "Telogreika" jacket

03 - field trousers

04 - boots

05 - 7,62 mm Mosin 91/30 rifle

06 - rifle oiler

07 - Model 1930 ammo pouches

08 - personal dressing

09 - military ID

10 - synthetic leather map pouch

Soviet infantry officer, 1943

01 - model 1943 "gimnastiorka" sweatshirt, officers' version

02 - model 1935 breeches

03 - model 1935 forage cap

04 - model 1940 helmet

05 - model 1935 officers' belt and webbing

06 - holster for the Nagant 1895 revolver

07 - map pouch

08 - officers' boots

Red Army officer, Reconnaissance unit, ca. 1943

01 - Model 1935 forage cap

02 - camouflage clothing, autumn variant

03 - 7,62 mm PPS-43 SMG

04 - tarpaulin ammo pouch for 3 PPS magazines

05 - Model 1935 officers' belt

06 - leather holster with 7,62mm TT pistol

07 - Model 1940 assault knife

08 - Adrianov compass

09 - personal dressing

10 - officers' boots

Thursday, February 19, 2015

ISU ASSAULT GUNS IN ACTION

A Soviet GAZ-MM 4 x 2 cargo truck drives past a line

of ISU-152 assault guns in Lvov, in the Ukraine, in July 1944. The

photograph gives a good view of the chassis' running gear, with

KV-l's spoked wheels rather than the disc wheels used on the T-34

and its variants.

The ISU-122 and ISU-152 were used in Independent Heavy Self-Propelled Artillery Regiments, which were awarded the Guards honorific after December 1944. By the end of the war there were 56 such units. Generally attached to the tank corps, they were deployed in the second echelon of an assault, providing long-range direct, and on occasion indirect, fire support to tanks in the first echelon, targeting German strongpoints and armoured vehicles. They were also vital in providing defensive antitank and artillery support for infantry.

The dual role of the ISU-152 is demonstrated by fighting on 15-16 January 1945 in the area of the Polish village of Borowe. Elements of Marshal K. K. Rokossovsky's 2nd Byelorussian Front were vigorously counterattacked by the Panzergrenadier Division Grossdeutschland. The initial German assault proved very effective, driving the Soviets back. As elements of the spearhead 2nd Fusilier Battalion consolidated their gains, the 3rd Fusilier Battalion moved through them towards Soviet positions around Borowe. Both battalions soon came under high explosive and armour piercing fire from SU-152s of the 390th Guards Independent Heavy Artillery Regiment. The 3rd Fusilier Battalion and its supporting armour did manage to secure the town on 16 January under intense antitank fire from SU-152 guns supported by rocket artillery. But success was short-lived, as Soviet success in other areas collapsed the front, forcing a withdrawal. Even so, as one soldier of the 2nd Battalion starkly described, being under fire from 'Black Pigs' was harrowing:

Black detonations in front of us, behind us, beside us - and we lay on the frozen ground with no possibility of crawling into it ... Now and then someone raised his face a little beneath his steel helmet to see if the other was alive. For an hour there was nothing but the sound of incoming and exploding shells.

During the 1st Ukrainian Front's breakout from the Sandomierz bridgehead over the river Vistula in central Poland, Marshal I. S. Konev used several ISU-equipped regiments to enhance the devastating opening barrage of 450 medium- and heavy field guns per kilometre of front. When the assault troops moved forwards, poor weather and lack of visibility in the harsh winter conditions made it difficult to operate with air and artillery support.

However, the momentum of the attack was maintained through the close fire support provided by ISU-122 and ISU-152s operating alongside the infantry. The result was an advance of 12km (7.45 miles) on the first day, carrying Soviet forces through the forward German tactical defences and creating the conditions for the release of the second echelon tank armies with their fast medium T-34s to exploit deep into the enemy's operational rear. This pattern of attack was a thorough vindication of pre-war Soviet ideas about the interaction of heavy and medium armour in carrying out the deep battle and deep operation respectively.

The ISU-122 and ISU-152 were used in Independent Heavy Self-Propelled Artillery Regiments, which were awarded the Guards honorific after December 1944. By the end of the war there were 56 such units. Generally attached to the tank corps, they were deployed in the second echelon of an assault, providing long-range direct, and on occasion indirect, fire support to tanks in the first echelon, targeting German strongpoints and armoured vehicles. They were also vital in providing defensive antitank and artillery support for infantry.

The dual role of the ISU-152 is demonstrated by fighting on 15-16 January 1945 in the area of the Polish village of Borowe. Elements of Marshal K. K. Rokossovsky's 2nd Byelorussian Front were vigorously counterattacked by the Panzergrenadier Division Grossdeutschland. The initial German assault proved very effective, driving the Soviets back. As elements of the spearhead 2nd Fusilier Battalion consolidated their gains, the 3rd Fusilier Battalion moved through them towards Soviet positions around Borowe. Both battalions soon came under high explosive and armour piercing fire from SU-152s of the 390th Guards Independent Heavy Artillery Regiment. The 3rd Fusilier Battalion and its supporting armour did manage to secure the town on 16 January under intense antitank fire from SU-152 guns supported by rocket artillery. But success was short-lived, as Soviet success in other areas collapsed the front, forcing a withdrawal. Even so, as one soldier of the 2nd Battalion starkly described, being under fire from 'Black Pigs' was harrowing:

Black detonations in front of us, behind us, beside us - and we lay on the frozen ground with no possibility of crawling into it ... Now and then someone raised his face a little beneath his steel helmet to see if the other was alive. For an hour there was nothing but the sound of incoming and exploding shells.

During the 1st Ukrainian Front's breakout from the Sandomierz bridgehead over the river Vistula in central Poland, Marshal I. S. Konev used several ISU-equipped regiments to enhance the devastating opening barrage of 450 medium- and heavy field guns per kilometre of front. When the assault troops moved forwards, poor weather and lack of visibility in the harsh winter conditions made it difficult to operate with air and artillery support.

However, the momentum of the attack was maintained through the close fire support provided by ISU-122 and ISU-152s operating alongside the infantry. The result was an advance of 12km (7.45 miles) on the first day, carrying Soviet forces through the forward German tactical defences and creating the conditions for the release of the second echelon tank armies with their fast medium T-34s to exploit deep into the enemy's operational rear. This pattern of attack was a thorough vindication of pre-war Soviet ideas about the interaction of heavy and medium armour in carrying out the deep battle and deep operation respectively.

IS-2 IN ACTION

The IS-2 was issued to Guards Heavy Tank Regiments from the start of 1944. The first unit equipped with them to see action was the 11th Guards Independent Heavy Tank Brigade in April in operations in the southern Ukraine, following the successful encirclement and destruction of German forces' in the Korsun-Shevchenkiovsky area. In 20 days of fighting, the 72nd Independent Guards Tank Regiment lost only eight IS-2s, whilst inflicting great loss on the enemy, although Soviet claims of 41 Tigers and Elephants is excessive and probably the result of mistaken identity. During this period of action, one IS-2 withstood five direct hits from the 8.8cm (3.46in) gun of an Elephant fired from 1500-2000m (1640-2187yd). The vehicle was eventually knocked out by another of these vehicles at 700m (765yd). The loss of other vehicles to fire and engine damage serves to highlight the point that even the most heavily armoured tank still has areas of vulnerability.

One of the IS-2's most notable engagements took place during the fighting in August 1944 to establish a bridgehead across the river Vistula around the town of Sandomierz. This was the first time that the IS-2 had come up against the fearsome Royal Tiger. During the engagement on 13 August, the 71st Independent Heavy Tank Regiment's 11 IS-2s blocked an attack by 14 Royal Tigers of the 501st Heavy Panzer Regiment. Engaging at 600m (656yd) coupled with skilled tactical handling saw four Royal Tigers destroyed and seven damaged, for the loss of three IS-2s and seven damaged. This was a very creditable performance, although post-battle analysis again revealed that the IS-2's armour was vulnerable up to 1000m (9144yd) because of faulty casting.

SOVIET NAVY WWII

Soviet destroyer Valerian Kuibyshev

(Northern fleet)

Soviet motor torpedo boats of D-3

type (Northern fleet)

Stalin at first looked to the United States for assistance in building a blue water fleet of battleships and battlecruisers. His request to commission a U.S. shipyard to build a battleship for the Soviet Navy was spurned. Stalin turned next to Adolf Hitler for technical aid, from the end of their partnership in conquering Poland in 1939 to the start of Hitler’s BARBAROSSA invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941. Stalin paid Hitler back by extending operational cooperation to the Kriegsmarine in its war with the Western Allies. A special naval base was set up for the Germans at Lista Bay near Murmansk that was used by the Kriegsmarine to facilitate the WESERÜBUNG invasion of Norway in April 1940, while several other Soviet ports were opened to German warships. The Soviets also aided transfer of a German auxiliary cruiser around Siberia to prey on Allied shipping in the northern Pacific. For this assistance the Kriegsmarine provided Moscow specialized naval equipment, ship schematics, and a partially completed cruiser in a form of barter exchange. This odd situation reflected Stalin’s long-term view of the need to build up Soviet naval power and misreading of the German Führer’s intentions. Stalin’s view contrasted sharply with Hitler’s belief that any short-term naval aid to Moscow would prove irrelevant once he unleashed his armored legions in the east.

The Baltic Red Banner fleet began the war with just two World War I–era battleships and two cruisers. These remained confined to the base at Kronstadt. It also had 19 destroyers and 65 submarines of varying quality, as well as a fleet air arm of over 650 planes. During the Finnish–Soviet War (1939–1940) the Baltic fleet moved to cut off Finland from sea lanes to Sweden, but no naval engagements ensued with Finnish surface ships. That changed with BARBAROSSA, as the Kriegsmarine joined the fight in the Baltic. The Germans moved dozens of minelayers, minesweepers, and other coastal warships to Finland before June 1941, and afterward established a major base in the port of Helsinki. Most naval action in the early part of the German–Soviet war in the Baltic was confined to laying sea mines, sweeping for mines, U-boat attacks, and aerial attacks by the Luftwaffe on exposed Soviet ships. There were several small Soviet and German amphibious clashes over a number of small islands. The major Soviet warship and transport losses came in August in one of the least known, although the worst, convoy actions of the entire war. The Soviets sought to relocate smaller warships from Tallinn to Kronstadt and to evacuate as many personnel by ship as they could before the Panzers arrived in the Estonian capital. In the German attack on the hastily formed Soviet convoy the Soviet Navy lost 18 small warships and 42 merchantmen and troopships, most to a night encounter with a dense minefield. The following day, as all major warships fled the convoy, Luftwaffe dive bombers struck floundering and exposed troopships and transports. Only two survived. Total loss of life was at least 12,000.

The naval garrison on Kronstadt held out for 28 months during the siege of Leningrad, then used its big guns to support the Red Army in the operation that finally broke the siege in January–February, 1944. Meanwhile, in 1942 the Soviet Navy went on the offense in the Baltic. It sent submarines deeper into the sea, where they enjoyed some success against German and Finnish shipping plying trade routes from Sweden and along the coastline of Germany. Several Swedish ships were sunk inadvertently, which moved the Swedish Navy to introduce a convoy system and on occasion to depth charge Soviet boats. The most successful Soviet naval operation in the Baltic was an amphibious lift of nearly 45,000 troops to Oranienbaum in 1944, during the offensive that lifted the siege of Leningrad. An even larger set of amphibious operations landed Red Army soldiers and Soviet Navy marines on a number of small, but key, islands in the Gulf of Riga in late 1944. The situation in the air was also reversed by 1944, as Red Army Air Force and Soviet Navy planes harassed and sank congested German shipping. From 1941 to 1945 the Soviet Baltic fleet lost one old battleship (to bombs), 15 destroyers, 39 submarines, and well over 100 minesweepers, smaller warships, and transports, as well as numerous landing craft. A modern battleship under construction before the war was locked in port by the siege of Leningrad and never completed.

The war began disastrously for the Soviet Navy’s Black Sea Fleet, which was bombed at anchor on the first day, June 22, 1941. Before that attack the Black Sea Fleet comprised a single modernized dreadnought, four cruisers, dozens of older and new destroyers, 47 old submarines, nearly 90 motor torpedo boats, and sundry coastal craft. It had 626 aircraft, mostly of obsolete types. The Black Sea Fleet was also responsible for the Caspian Sea, the Sea of Azov, and patrolling the lower Don and Volga Rivers. A 59,000 ton giant super battleship, the “Sovetskaia Ukraina,” was still under construction when the bombs started to fall, just like its sister ship in Leningrad. When Army Group South took the port of Nikolaev during the Donbass-Rostov operation, the “Sovetskaia Ukraina” was captured. Once the terrible siege of Sebastopol began, the Fleet’s main port was closed to naval operations and ships scrambled to relocate to ports farther east. The first Black Sea Fleet amphibious operation was a landing of 2,000 marines behind Rumanian lines near Odessa, a desperate action that failed to save the city. Instead, between October 1–16, 1941, an evacuation of over 86,000 soldiers and 14,000 other Soviet citizens was carried out from Odessa. The Fleet facilitated large-scale amphibious landings at Kerch-Feodosiia in December 1941. Without effective Kriegsmarine opposition in the Black Sea, the Soviets took the Germans in the Crimea by surprise. They came ashore in force, over 40,000 strong, at more than two dozen locations behind the main enemy force, which was investing Sebastopol. More troops were sent in via an ice road over the Kerch Straits. A larger amphibious and airborne operation was planned to retake the entire Crimean peninsula in January 1942, but it was canceled when the situation badly deteriorated. When the Germans assaulted in May with their main force, relocated from Sebastopol, the Soviet Navy evacuated survivors across the Kerch Straits.

All this time, the Black Sea Fleet maintained a 240-mile lifeline into Sebastopol under constant and heavy Luftwaffe attack. By late 1942 the Fleet faced German and Italian small craft flotillas that were shipped overland and reassembled in the Crimea. The Soviets also faced at least six Axis submarines in the Black Sea, including one from Rumania. In February 1943, the Soviets carried out two amphibious landings around Novorossisk. The smaller landing established a beachhead that held on, and was successfully reinforced by sea. On September 10 the port fell when Black Sea Fleet leaders used over 130 small boats to enter and assault the harbor. However, in October the Fleet lost three new destroyers to land-based bombers, after which Stalin forbade its commanders to expose any surface ships to danger. More landings were made in German rear areas to block the Wehrmacht on its long retreat out of the east. These were mostly wasteful of Soviet lives and forces. Worst of all, the Soviet Navy failed to prevent evacuation of over 250,000 Axis troops of Army Group A across the Kerch Straits during September–October, 1943. That was mostly Stalin’s fault: he refused to expose any large surface ships to German bombing, lest they be lost. That lessened the victory at Sebastopol achieved by Soviet ground forces in May 1944: a flotilla of small ships and barges was massively bombed and shelled, but 130,000 German and Rumanians escaped who could have been stopped by the big guns of destroyers, cruisers, and the Fleet’s unopposed dreadnought that Stalin would not allow into action.

Pacific Fleet operations were minimal and strictly defensive until the Manchurian offensive operation (August 1945). Most submarines were therefore released for service in the North Sea. To get there, they made a remarkable voyage across the Pacific, down the coast of North America, through the Panama Canal, and across the Atlantic to Murmansk or Archangel. Not all survived the journey. Those that did took up duty scouting for and protecting arctic convoys from Britain. In September 1943, the Soviet Navy was denied any ships surrendered by the Regia Marina to the Royal Navy at Malta. They went to the British instead. The Soviets did acquire a number of German surface ships in late May 1945, along with a share in those U-boats that were scuttled by their captains or sunk by the Western Allies

Suggested Reading: Jürgen Rohwer and Mikhail Monakov, Stalin’s Ocean-Going Fleet (2001).

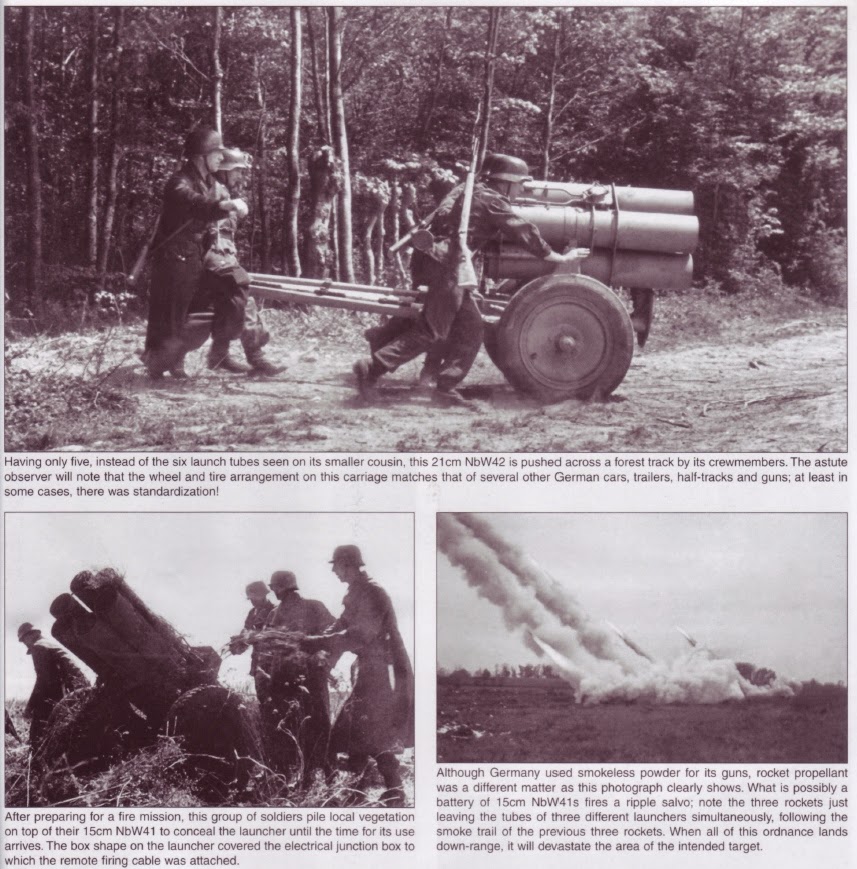

Nebelwerfer rocket launcher.

A diagram of the new Nebelwerfer

150mm ammunition

These rockets were fired from a six-tube launcher mounted on a towed carriage adapted from the 3.7 cm PaK 36 carriage. This system had a maximum range of 6,900 metres (7,500 yd). I am uncertain whether these weapons were used in the Western Desert, but photographs record them in Tunisia, Sicily and Italy, Normandy and the NWE campaign, and of course on the Russian front. Nearly five and a half million 15 cm rockets and six thousand launchers were manufactured over the course of the war.

The 15-cm (5.9-in) German artillery rockets were the mainstay of the large number of German army Nebelwerfer (literally smoke-throwing) units, initially formed to produce smoke screens for various tactical uses but later diverted to use artillery rockets as well. The 15-cm (5.9-in) rockets were extensively tested by the Germans at Kummersdorf West during the late 1930s, and by 1941 the first were ready for issue to the troops.

The 15-cm (5.9-in) rockets were of two main types: the 15-cm Wurfgranate 41 Spreng (high explosive) and 15- cm Wurfgranate 41 w Kh Nebel (smoke). In appearance both were similar and had an unusual layout, in that the rocket venturi that produced the spin stabilization were located some two-thirds of the way along the rocket body with the main payload behind them. This ensured that when the main explosive payload detonated the remains of the rocket motor added to the overall destructive effects. In flight the rocket had a distinctive droning sound that gave rise to the Allied nickname 'Moaning Minnie'. Special versions were issued for arctic and tropical use.

The first launcher issued for use with these rockets was a single-rail device known as the 'Do-Gerät’ (after the leader of the German rocket teams, General Dornberger). It was apparently intended for use by airborne units, but in the event was little used. Instead the main launcher for the 15-cm (5.9-in) rockets was the 15-cm Nebelwerfer 41. This fired six rockets from tubular launchers carried on a converted 3.7-cm Pak 35/36 anti-tank gun carriage. The tubes were arranged in a rough circle and were fired electrically one at a time in a fixed sequence. The maximum range of these rockets was variable, but usually about 6900m (7,545 yards), and they were normally fired en masse by batteries of 12 or more launchers. When so used the effects of such a bombardment could be devastating as the rockets could cover a considerable area of target terrain and the blast of their payloads was powerful.

On the move the Nebelwerfer 41s were usually towed by light halftracks that also carried extra ammunition and other equipment, but in 1942 a half-tracked launcher was issued. This was the 15-cm Panzerwerfer 42 which continued to use the 15-cm (5.9-in) rocket with the launcher tubes arranged in two horizontal rows of five on the top of an SdKfz 4/1 Maultier armoured halftrack, These vehicles were used to supply supporting fire for armoured operations. Up to 10 rockets could be carried ready for use in the launcher and a further 10 weapons inside the armoured body. Later in the war similar launchers were used on armoured schwere Wehrmachtschlepper (SWS) halftracks that were also used to tow more Nebelwerfer 4 Is, The SWS could carry up to 26 rockets inside its armoured hull.

The 15-cm (5.9-in) rockets were also used with the launchers intended for the 30-cm (11.8-in) rockets, with special rails for the smaller rockets fitted into the existing 30-cm (11.8-in) launcher rails.

#

PRO document WO 291/2317, "German use of the multi-barrelled rocket projector", dated 07 Jan 1944, has a couple of things to say on this question.

It gives safety zones from several sources. A German circular dated March 1942 gives safety zones for own troops for 15cm rockets as 500m in range and 300m in line from each edge of the target area, and says that concentration of own troops should be avoided for 3000 metres short of the target. Other reports give safety zones of 500 yards and 600 metres.

It also gives the results of three firing trials with captured rockets:

15cm Nebelwefer trial in North Africa

Rounds QE Mean range (m) m.d. dispersion in range (m)

10 6° 3' 2710 252

5 30° 7018 130

5 45° 7723 115

15cm HE trial in North Africa

Rounds QE Range (yds) m.d. range (yds) m.d. line (yds)

10 6° 3' 2954 247 77

4 30° 7675 142 37

5 30° 8446 127 34

Trial in England, 15cm HE and smoke

Type Rounds QE Range (yds) m.d. range m.d. line time of flight (secs)

HE 22 15° 4565 107 42 17.73

Smoke 15 15° 3509 117 33 13.60

PRO document WO 232/49, "Role of rockets as artillery weapons", says that with Land Mattress the dispersion in range approaches that of guns, but in line is still six times as much. It also says that the safety zone for Land Mattress is 500 yards.